The Lost Flag of the Land of Enchantment

#007: What happened to New Mexico's first (and worst) state flag?

Dear Reader,

When a friend sent me the image below and claimed it was New Mexico’s original state flag from 1915, I had the same reaction as you undoubtedly do: What? No. That can’t possibly be true.

Figure I. DrRandomFactor, Reconstruction of the “Twitchell Flag” of New Mexico, ca. 1915, uploaded January 2016

It is, in fact, a painstaking recreation by determined Wikipedia user and self-described “amateur cartographer” DrRandomFactor using modern photo-editing software.1 Unfortunately, this and other reconstructions of the so-called “Twitchell flag” (designed by turn-of-the-century New Mexico luminary Ralph Emerson Twitchell) have recently come in for some heat on the Internet. One Reddit user described the flag as “the vexillological equivalent of putting off the assignment until the night before it’s due.”2

Fair enough. Graphic design wasn’t Ralph Emerson Twitchell’s passion—New Mexico was. Twitchell moved to the then-territory as a young railroad lawyer in the 1880s and fell in love. In 1897, he was appointed a colonel in the territorial militia, and proudly went by “Colonel Twitchell” for the rest of his life.3 As he built his fortune and political influence, he devoted himself to studying New Mexico’s Spanish colonial history, ultimately producing nine books and multiple articles on the topic.4

Figure II. Ralph Emerson Twitchell, 1907

Twitchell also worked tirelessly for more than twenty years to promote New Mexico statehood.5 Yet when New Mexico finally joined the Union in 1912 after almost half a century as a U.S. territory, it was California, strangely enough, that would provide the setting to celebrate statehood in grand style.

Both San Diego and San Francisco were planning rival expositions—months-long fairs that were practically little cities of their own with elaborate buildings and entertainments—to commemorate the projected opening of the Panama Canal in 1914.6 New Mexico would be the newest state to have a pavilion of its own at San Diego’s Panama-California Exposition, and needless to say, Ralph Emerson Twitchell’s hands would be all over it.7

Twitchell eagerly assumed the role of president of the New Mexico Exposition Board, aided by the equally energetic newspaperman and publicist A.E. Koehler. The challenges were great; the budget was tiny. Twitchell and other board members paid their own expenses out of pocket, and he recalled in his final report to the governor how he had to become “an expert in architecture and exposition construction” as well as fundraising in order to bring the New Mexico Building and its exhibits to life.8

At the stroke of California midnight on January 1, 1915, however, it was obvious that Twitchell and the Exposition Board’s efforts to promote their state had paid off. A bleary President Woodrow Wilson (it was 3 a.m. Washington time) pressed a Western Union telegraph button and switched on the exposition’s lights from across the country, revealing the fairgrounds in all their glory to thirty-thousand-plus eager, confetti-throwing spectators.9

Figure III. New Mexico Building, San Diego Exposition, 1915

New Mexico’s building, unique among the fair’s Spanish Gothic architecture, was modeled on a Spanish mission along the Santa Fe trail.10 Its movie theater showing scenes of New Mexican life, its “spacious verandahs,” and its wide lawn planted with New Mexico wildflowers provided the perfect place to relax from the excitement of the fair.11 According to Twitchell’s 1916 report to the governor, 100,000 tourists visited New Mexico in 1915 and 50,000 decided to move to the state as a result of the publicity engendered by New Mexico’s presence at the fair.12

As a devoted Republican Party operative and personal friend, Twitchell even secured a special appearance from former president Teddy Roosevelt in July 1915. After all, Roosevelt had a special place in his heart for New Mexico: the territory had provided a significant percentage of Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” volunteer cavalry regiment during the Spanish-American War. Twitchell made a special trip back to Santa Fe in the midst of the expo to round up former Rough Riders for the occasion.13

But the heroes of San Juan Hill weren’t just a photo op. Twitchell and publicist Koehler had actually consulted with both Spanish-American War and Union Army veterans to help with a special project before the exposition opened: creating a New Mexico flag for the fair.14 The final design had a turquoise background “emblematic of the blue skies of New Mexico,” a miniature United States flag in the top left corner, “47” in the top right corner to acknowledge its position as the forty-seventh state to join the Union, the words “NEW MEXICO” in the middle, and the state seal with the motto “The Sunshine State” in the lower right corner.15

Figure IV. Twitchell flag (or re-creation), New Mexico Museum of History

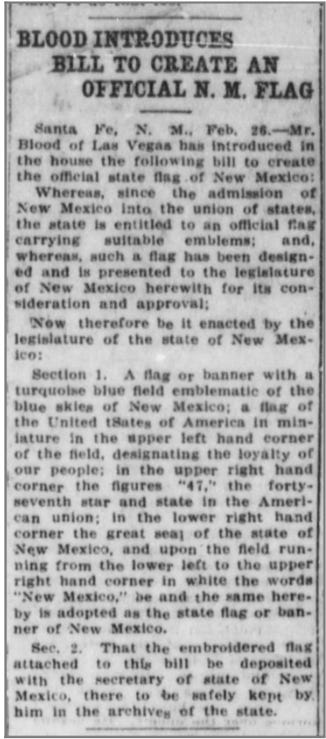

On February 25, 1915, Representative F.O. Blood of Las Vegas introduced “An Act adopting a State Flag for the State of New Mexico” in the New Mexico House of Representatives. “Freakish was the fortune of the state flag bill,” the Albuquerque Journal recalled two years later. “The design…was opposed by club women and others because of its bizarre composition and colors.” After “[hanging], limp as a dish rag” on the House’s calendar until the very end of the legislative session, the flag bill passed unanimously.16

It encountered more opposition in the state senate. “There appeared not to be a single ‘Yes’ [vote]” until the senator who had brought the bill to the floor shouted a rousing “Let’s do this for Twitch!” The first “No” vote changed his mind with a contrite “I didn’t know that this is for Twitch.” Equally chastened at the prospect of letting down their beloved Colonel Twitchell, the other “No”s then switched their votes, too, and New Mexico had its first state flag.17

Figure V. The bill to adopt a state flag for New Mexico, February 25, 1915

The bill was accompanied by a presentation flag (handmade by a “lady friend” of Colonel Twitchell): “a superbly worked banner on silk poplin” embroidered with colored silk and Native New Mexico crystal.18

According to the bill, the flag was to “be deposited with the secretary of state of New Mexico, there to be safely kept by him in the archives of the state.” In 1954, New Mexico Secretary of State Beatrice Roach donated the presentation flag to the New Mexico Museum (now the New Mexico History Museum). The flag, long since faded to white, was already regarded as a “forgotten museum piece” by 1963.19 New Mexico had moved on.

Figure VI. First official New Mexico state flag, ca. 1915

In 1924, the New Mexico chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution announced that it would sponsor a contest for a new state flag design.20 The announcement did not touch on the deficiencies of the Twitchell flag, but the Santa Fe New Mexican probably captured the mood a few years later in its description of “the old, somewhat conglomerate ‘blue-sky’ flag” of yore.21

Archaeologist Harry Mera won the day “by a more or less desultory popular vote” with a design executed by his wife. It was simple, arresting, and nowadays, instantly recognizable: an ancient sun symbol used by the Zia people, rendered in crimson on a gold background in homage to the colors of imperial Spain.22

Like the previous state flag, however, Mera’s design was not without controversy. The Zia flag was the clear favorite when the Santa Fe Kiwanis Club met in February 1925 to review the contest submissions. Nevertheless, “some [attendees] thought the state flag should…contain the national colors; others thought [New Mexico] should follow the conventional example and have the state seal on the flag; still others suggested that the name of the state or the initials “‘N.M.’ should be on it somewhere.”23

By the end of February, two camps had emerged: “one holding that [the flag] should consist merely of the state seal with any appropriate color of background; the other that it should be a distinctive ensign embodying something of the traditions of the state.”24 Should New Mexico embrace its unique heritage with Mera’s design, or honor its place in the Union by attempting to harmonize with the majority of other state flags?

Figure VII. New Mexico state flag, 1925-present

Ralph Emerson Twitchell—who loved New Mexico’s storied past and the exciting promise of its future as the forty-seventh state—apparently did not take an active role in the debate over the new flag. His health was ailing; he would die in August 1925 after being rushed to California for emergency medical treatment.25 A new flag flew over New Mexico, and a new era had begun.

Sincerely,

SOURCES

Primary

“$25 Prize for Best Design State Flag.” The Lordsburg Liberal (Lordsburg, New Mexico). November 27, 1924, page 4. Accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/1023016020/.

“100 Years Later Electriquettes Return To Balboa Park.” Sandiegoville.com. March 28, 2016. https://www.sandiegoville.com/2016/03/100-years-later-electriquettes-return.html.

“Colonel Ralph E. Twitchell Dies in Los Angeles and State Mourns,” Santa Fe New Mexican, August 26, 1925, page 1, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583745683/.

“The Exposition Board Made a Great Success,” New Mexico State Record (Santa Fe, NM), December 22, 1916, page 1. Accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/896383915/.

Flint, R.F. “Story of the Making of the Sunshine State.” The Dickinson Press (Dickinson, Stark County, D.T. [i.e N.D.]). November 20, 1915, page 17. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88076013/1915-11-20/ed-1/seq-17/.

“The Flag Bill.” Albuquerque Journal (Albuquerque, NM). March 13, 1917, page 2.

Gravure section. Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.). December 30, 1928, page 77. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1928-12-30/ed-1/seq-77/.

House Journal: Proceedings of the Second State Legislature, State of New Mexico, January 12th to March 13th, 1915, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Santa Fe: New Mexico Secretary of State, n.d.

Keystone Film Company. “A glimpse of the San Diego Exposition.” Dir. Sennett, Mack, Ection. United States: Keystone, 1915. Film. Accessed online through the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/00563595/.

“The New Mexico Exhibit is Attracting Attention.” Deming Graphic (Deming, NM). February 12, 1915. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063579/1915-02-12/ed-1/seq-4/.

Senate Journal: Proceedings of the Second State Legislature, State of New Mexico, January 12th to March 13th, 1915, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Santa Fe: New Mexico Secretary of State, n.d.

The Official Guidebook of the Panama-California Exposition, San Diego 1915. San Diego, National Views Company, ca. 1914. Accessed online through the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/17002751/.

“Roosevelt to Be Attraction at New Mexico Day.” Albuquerque Morning Journal (Albuquerque, NM). June 17, 1915, page 3. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84031081/1915-06-17/ed-1/seq-3/.

S.R. Parke. “S-Parke-Lets.” Brewery Gulch Gazette (Bisbee, AZ). January 13, 1938, page 3. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89070012/1938-01-13/ed-1/seq-3/.

“The State Flag.” The Santa Fe New Mexican. February 4, 1925, page 4. Accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583603700/.

“The State Flag.” The Santa Fe New Mexican. February 27, 1925, page 4. Accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583603971/.

“Sunshine State.” The Madison Daily Leader (Madison, S.D.). March 10, 1919, page 2. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88076013/1915-11-20/ed-1/seq-17/.

“TR and Mrs. Roosevelt [at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915].” Video. Accessed online through the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/mp76000120/.

“Women Register Firm Protest on New State Flag.” Santa Fe New Mexican (Santa Fe, NM). March 17, 1915, page 3. Accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583669810/.

Secondary

Amero, Richard W. “The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915.” The Journal of San Diego History: San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 1 (Winter 1990). Accessed online through the San Diego History Center: https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1990/january/expo/.

“The Southwest on Display at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915.” The Journal of San Diego History: San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4 (Fall 1990). Accessed online through the San Diego History Center: https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1990/october/amero/.

Jenkins, Myra Ellen. “A Dedication to the Memory of Ralph Emerson Twitchell, 1859-1925.” Arizona and the West, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer, 1966), pp. 103-106. Accessed online through JStor: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40167196.

Nathanson, Rick. “New Mexico Flag Hasn't Always Had a Zia Symbol; Earliest Version Boasted Quartz Crystals.” Albuquerque Journal [Albuquerque, NM]. June 14, 2005. Accessed online through the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/web/20210304203233/https://www.abqjournal.com/news/state/361879nm06-14-05.htm.

Reynolds, Christopher. “How San Diego’s, San Francisco’s rival 1915 expositions shaped them.” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, CA). January 3, 1915. Accessed online through the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/web/20240910071134/https://www.latimes.com/travel/california/la-tr-d-sd-sf-1915-panama-expos-20150104-story.html.

Simmons, Marc. “The story behind N.M. history author.” Santa Fe New Mexican (Santa Fe, NM). August 30, 2008, pages C001 and C-3.

Smith, Whitney. The Flag Book of the United States. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1970. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/flagbookofunited00smit/page/152/mode/2up.

Twitchell, Daniel Jason. Ralph Emerson Twitchell: The Man Who Found New Mexico’s Future in the Past. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2018.

DrRandomFactor, “Flag of New Mexico (1912–1925),” Wikpedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_New_Mexico#/media/File:Flag_of_New_Mexico_(1912%E2%80%931925).svg.

DrRandomFactor cites as inspiration the illustration on page 152 of Whitney Smith’s The Flag Book of the United States (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1970).

ArelMCII, “The vexillological equivalent of putting off the assignment until the night before it's due,” ca. January 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/vexillology/comments/1hw27tx/1915_twitchell_flag_of_new_mexico_created_for_the/.

Myra Ellen Jenkins, “A Dedication to the Memory of Ralph Emerson Twitchell, 1859-1925,” Arizona and the West, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer, 1966), pp. 103-106, 103.

Historian Marc Simmons notes that Twitchell’s collected works on New Mexico weigh over 20 pounds (See Simmons, “The story behind N.M. history author,” Santa Fe New Mexican [Santa Fe, NM], August 30, 2008, pages C001 and C-3). Although foundational to the study of New Mexico history, Twitchell’s works have since come under some scrutiny for various lapses in historical propriety.

This was to an extent true even in his own day; it was only from 1911 on that “Twitchell, sensitive to criticism that [in his previous works] he had neither given credit to other authors not cited sources for his facts,” condescended to using footnotes. See Jenkins, 105, et passim.

See Daniel Jason Twitchell, Ralph Emerson Twitchell: The Man Who Found New Mexico’s Future in the Past (Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2018), 77, for a summary of Twitchell’s pro-statehood activism.

Turn of the century Americans went crazy for expositions the way modern Americans go crazy for sitting at home and staring at their phones. Both San Diego and San Francisco began plotting their Panama Canal expositions in 1909. (New Orleans also tried to get in on the action in 1910, but was quickly squeezed out by the Californians.) San Diego and San Francisco both attempted to wrangle Congress into favoring their particular city with official recognition. The more populous San Francisco won out, but San Diego resolved to go ahead—although it agreed to drop “international” from its fair’s official name. The San Diego expo opened almost two months before San Francisco’s and would stay open an additional year.

See Christopher Reynolds, “How San Diego’s, San Francisco’s rival 1915 expositions shaped them,” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, CA), January 3, 1915, accessed online through the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/web/20240910071134/https://www.latimes.com/travel/california/la-tr-d-sd-sf-1915-panama-expos-20150104-story.html and Richard Amero, “The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915,” The Journal of San Diego History: San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 1 (Winter 1990), accessed online through the San Diego History Center: https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1990/january/expo/.

Arizona also became a state in 1912 but did not participate in the San Diego Panama-California Exposition for reasons I haven’t been able to figure out. Dear Readers, if either one of you has additional information about this, you know where to find me.

“The Exposition Board Made a Great Success,” New Mexico State Record (Santa Fe, NM), December 22, 1916, page 1.

Amero, “The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915” and “The Southwest on Display at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915.” The Journal of San Diego History: San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4 (Fall 1990), accessed online through the San Diego History Center: https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1990/october/amero/.

An advertisement in the Santa Fe New Mexican—no doubt with the advice of publicity wiz Koehler—was careful to note that this mission, the Rock of Acoma, was “150 years older than the oldest California mission” (Santa Fe New Mexican, March 17, 1915, page 7, accessed through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583669856/).

Deming Feb 12. Visitors toodling around the San Diego fairgrounds in the specially designed wicker motorcars dubbed “electriquettes” could enjoy rides, performances, concessions, and such sites as a model California farm, a model Southwest Indian village, a model Marine encampment, and a model opium den (see Richard Amero, “The Southwest on Display”).

Twitchell apparently got in trouble with the Pueblo of Taos, New Mexico for secretly filming a ritual dance (against their express wishes) so that it could be shown at the fair. The film was stolen from the New Mexico building in July 1915, but an undeterred Twitchell simply replaced the reel with a backup. See Daniel Jason Twitchell, 121. For the incident, Twitchell cites Matthew Bokovoy, The San Diego World’s Fairs and Southwestern Memory, 1880-1940 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 132-134. Guess I should have read that book, too. Oh, well. You can’t have everything.

“The Exposition Board Made a Great Success,” New Mexico State Record.

“Roosevelt to Be Attraction at New Mexico Day,” Albuquerque Morning Journal (Albuquerque, NM), June 17, 1915, page 3, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84031081/1915-06-17/ed-1/seq-3/.

You can see a clip of Teddy Roosevelt at the fair here (and could that be Colonel Twitchell over T.R.’s left shoulder, or another distinguished balding man?):

Heck, while you’re here, why don’t you do some exploring yourself? Glimpse an authentic electriquette in action at 3:53 and silent film star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle hamming it up for the camera at 4:42.

“Women Register Firm Protest on New State Flag,” Santa Fe New Mexican (Santa Fe, NM), March 17, 1915, page 3.

Do you feel guilty for thinking this flag is ugly now that you know it was designed by veterans? Do you hate our troops? Explain.

According to the website of the New Mexico Secretary of State, Florida wouldn’t officially become the “Sunshine State” until the 1950s. A quick glance through Chronicling America reveals that no fewer than five states have apparently laid claim to the title over the years: Florida, New Mexico, California, North Dakota, and South Dakota. In 1938, the Bisbee, Arizona Brewery Gulch Gazette mused, “If New Mexico is a Sunshine state, what would you call Arizona? Perpetual Sunshine State?”

I know that isn’t a proper investigation, but frankly, I’m tired. You’re tired. Let’s not do this right now, okay?

“The Flag Bill,” Albuquerque Journal (Albuquerque, NM), March 13, 1917, page 2.

Ibid. Perhaps we ought to take this touching tale with a grain of salt. The author claims that the flag bill “was introduced as house bill [sic] 271,” but the official journal of the legislature of New Mexico records it as House Bill 319. Moreover, the senator who moved to pass the bill was one Herbert B. Holt of Las Cruces, not Senator Baird as per the 1917 article (“Fifty-Seventh Day - Tuesday, March 9th, 1915,” Senate Journal: Proceedings of the Second State Legislature, State of New Mexico, January 12th to March 13th, 1915, Santa Fe, New Mexico [Santa Fe: New Mexico Secretary of State, n.d.], 303). Baird does not even appear in the list of state senators at the beginning of the official Senate Journal for this term. AN: I may add more detail about these proceedings later, if I can be bothered. If I can’t and you’re curious, email me or leave a comment to remind me to do it.

The passage of the bill in both houses did nothing to dim the protests of various women’s groups, who immediately called a conference with the governor and Colonel Twitchell. The women asked for two years to come up with a state flag design of their own. Twitchell, irritated, “suggested that since the design had been already adopted, it might be ‘amended’ at the next [legislative] session.” The amused governor, meanwhile, “appeared to be enjoying the proceedings” (“Women Register Firm Protest on New State Flag,” Santa Fe New Mexican).

“Outside of that, Colonel Twitchell, the state flag is considered by the ladies to be a thing of beauty and a joy forever,” the Santa Fe New Mexican’s editorial board sniped the following day (Santa Fe New Mexican, March 1, 1915, page 6).

“Bridge Bills Killed at Morning Session,” Albuquerque Journal (Albuquerque, New Mexico), February 24, 1915, page 1.

Howard Bryan, “Off the Beaten Path,” The Albuquerque Tribune, May 9, 1963, page 22, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/783175913/.

Huge thank you to Hannah Abelbeck and Mark Dodge of the New Mexico History Museum for corresponding with me about the Twitchell flag and confirming that this is the same flag donated by Mrs. Roach in 1954!

For an image of the flag in 1963, see below (from the article cited above). There are apparently “four white bone rings” (per museum records) at the top of the flag, indicating that it was designed to hang like a banner rather than fly from a flagpole.

“$25 Prize for Best Design State Flag,” The Lordsburg Liberal (Lordsburg, New Mexico), November 27, 1924, page 4, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/1023016020/.

“The New Mexico Flag,” Santa Fe New Mexican, June 19, 1926, page 4, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583768663/.

Ibid.

“The State Flag,” The Santa Fe New Mexican, February 4, 1925, page 4, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583603700/. As in 1915, a group of ladies stormed the Capitol in Santa Fe to protest the new flag design. See “New Mexico Flag,” Santa Fe New Mexican.

“The State Flag,” The Santa Fe New Mexican, February 27, 1925, page 4, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583603971/.

“Colonel Ralph E. Twitchell Dies in Los Angeles and State Mourns,” Santa Fe New Mexican, August 26, 1925, page 1, accessed online through Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/image/583745683/.

Thank you for reading. As always, this has been a waste of my time. Please don’t mind me if I stealth edit some citations later for uniformity.