Dear Reader,

If it were the early 19th century, and you had just bitten James Madison’s finger down to the bone, you would probably expect some kind of punishment.

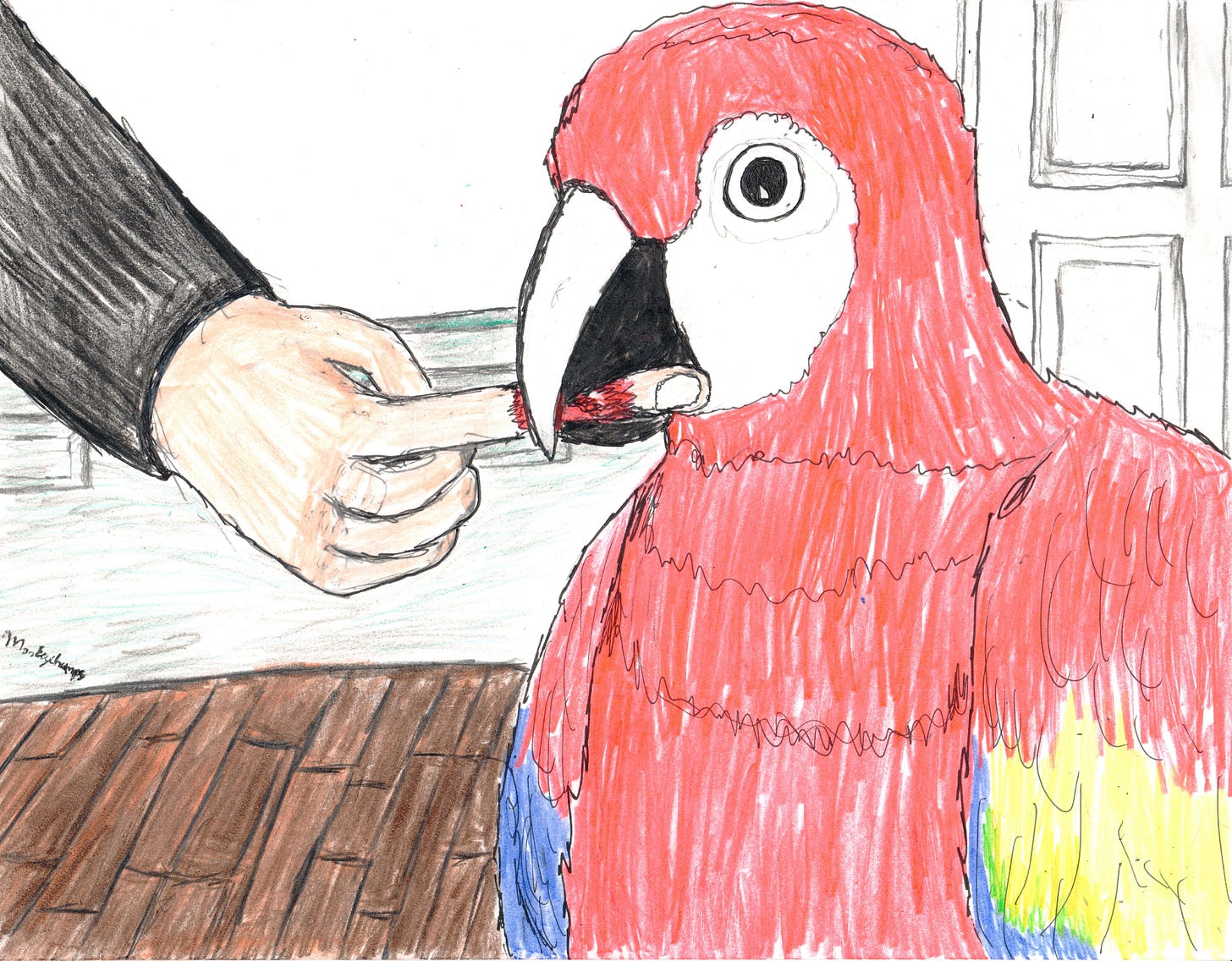

That is because you are not Dolley Madison’s evil pet macaw. A Madison family friend recalled that the Father of the Constitution “took [the assault] in perfect good humor, as only pretty Polly’s way.”1 As only pretty Polly’s way. Let’s keep in mind that our fourth president stood only 5 (brilliant!) feet and three (scintillating!) inches tall, and that macaws like the one owned by his wife can grow to be more than half that size.2 Nevertheless, “little Jemmy” took on the role of protecting guests from Polly’s “formidable beak and claws,” and it was during a heroic rescue attempt sometime in the 1820s that his finger met with her bone-crushing fury.3

(Sure, Madison may not have done a great job defending the nation’s capital against the British during the War of 1812. But had an enormous parrot marched on the city? Maybe the original White House would still be standing.)

Polly was presented to Dolley by an unidentified “South American Diplomat” around 1813 and bonded quickly with both the Madisons and the White House’s French steward.4 This proved to be a good career move. As the British approached Washington in August 1814, ready to burn and plunder our national treasures, Polly was among the items the steward helped save from the White House (Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington being another, but Polly had the advantage of doubling as a weapon).5

An excellent record of Polly’s evil deeds has been compiled by researcher Hilarie M. Hicks for the website of Montpelier, the Madison family estate. If you visit Montpelier today, you can experience a tamer version of Polly’s reign of terror: the staff now moves a stuffed macaw around the mansion to frighten delight and educate visitors.6

But what about our other presidents? George Washington himself owned many birds over the course of his life and presidency, some of which were doubtless ill-tempered. As historian Mary V. Thompson writes in a post for Mount Vernon, Washington’s earliest recorded purchase of a parrot was in April 1773, mere months before the Boston Tea Party and well into a prevailing colonial grumpiness.7

This and subsequent birds most likely belonged to Washington’s wife Martha and her children and grandchildren. Nelly Custis (Martha’s granddaughter; Washington’s step-granddaughter) was particularly proud of the green parrot she kept in the Presidential mansion in Philadelphia.8

Washington, though, wasn’t an admirer. In 1787, as his presidency wound down and the family prepared to go back to Virginia, he wrote to his secretary that “On one side I am called upon to remember the Parrot, on the other to remember the dog. For my own part I should not pine much if both were forgot.”9 Typical dad in packing mode, you might say. But could this be an indication that even beyond its horrible squawking of “non, non, non, pauvre Madelon” (the refrain of the song Nelly taught it), the green parrot had darker habits?10 The dog was certainly no good. A few months later, it apparently bit an enslaved young man named Christopher and then died of “Madness.”11

Polly Madison seems to have met her own fate sometime towards the middle of the nineteenth century. She disappeared one night from Montpelier’s front porch, perhaps carried off by a larger bird. One can only imagine the hell Polly was for Montpelier’s enslaved household servants, who were tasked with bringing her to her perch every evening for thirty years. Could someone have quietly gotten rid of the aging and spiteful Polly for the good of the rest of the household?12

As the bones of Dolley Madison’s cherished macaw bleached somewhere atop Virginia’s mountains in 1845, another dastardly presidential bird attempted to live up to her disgraceful legacy. According to the much later recollections of a teenage attendee at Andrew Jackson’s funeral, “a wicked parrot that was a household pet [of the Jacksons], got excited and commenced swearing so long and loud as to disturb” those paying their respects.13

By the late nineteenth century, William McKinley supposedly had a parrot called “The Washington Post,” although I have yet to track down contemporary evidence of its existence.14 A Vermont newspaper item from 1902 reports that McKinley’s “favorite parrot” was a yellow-headed Amazon named Loretta. She “used to amuse the president by singing” a popular racist song (albeit one written by black composer Ernest Hogan) whenever she saw a black person. Apparently the president was the only one to find her amusing; after McKinley’s assassination she was banished to the pet store.15 Even bird-loving Teddy Roosevelt regarded his son’s powerful hyacinth macaw, Eli Yale, “with dark suspicion.”16 Yet none of these (literally) colorful characters can claim the same level of sustained physical violence as Dolley Madison’s “pretty Polly.”

It was only her way.

Sincerely,

Miss Remember

YOUR HOMEWORK

Come up with a plausible candidate for the South American diplomat who inflicted Polly on a suffering nation. You may find this article from Founders Online a helpful starting point. Send completed assignments to missremember@substack.com.

APPENDIX A: JUDITH WALKER RIVES ON POLLY

“I might, indeed, run some risk of associating myself with the great parrot presented to Mrs. Madison by a South American Diplomat; and who, notwithstanding her magnificent plumage was an object of special terror to me. Mr. Madison soon perceived the jealousy of Mrs. Poll, and watched with the most amiable assiduity every opportunity of interposing his authority to save me from her formidable beak and claws. On one occasion, when he came to the rescue, she bit his finger to the bone, —a catastrophe which gave me real sorrow, though he took it in perfect good humor, as only pretty Polly’s way.”

Judith Walker Rives [Mrs. William Cabell Rives], manuscript autobiography, Library of Congress MSS 37937, William C. Rives papers, Box 130, autobiography page 56.

APPENDIX B: MARY ESTELLE ELIZABETH CUTTS ON POLLY

“[Dolley Madison] had one pet brought with her [to Montpelier] from Washington, a large Macaw—it was a splendid bird and seemed happy and proud when it spread its wings and screamed out its French phrases, which it had been taught by [White House steward] John Sioussa—It was very fond of Mr. and Mrs. Madison, but the terror of visitors. ‘Polly is coming!’ was the mode of frightening the children of the household as some of those little ones now grown can tell! She was very old, and her career was recently brought to an end by a night hawk, which pounced upon her, when, one night by the carelessness of servants, she was not brought to her perch in the hall.”

Mary Estelle Elizabeth Cutts, Mary Cutts Memoir II, as published in The Queen of America: Mary Cutts’s Life of Dolley Madison (ed. Catherine Allgor) (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 159, accessed online through the Internet Archive: The queen of America : Mary Cutts's life of Dolley Madison : Cutts, Mary Estelle Elizabeth, 1814-1856 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

[AN: In reproducing this quotation I have lowered superscripted letters, elided cancelations, and adopted additions, all of which are visible in the source linked above.]

SOURCES

PRIMARY

Cutts, Mary Estelle Elizabeth. Mary Cutts Memoir II. As published in The Queen of America: Mary Cutts’s Life of Dolley Madison (ed. Catherine Allgor) (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), pp. 133-196. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: The queen of America : Mary Cutts's life of Dolley Madison : Cutts, Mary Estelle Elizabeth, 1814-1856 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

Jennings, Paul. A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison. Brooklyn: George C. Beadle, 1865. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: A colored man's reminiscences of James Madison (archive.org).

Jonson, Benjamin. Ben: Jonson his Volpone or the Foxe. London: Thomas Thorppe, 1607. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: Ben: Jonson his Volpone or the foxe. 1607 : Jonson, Benjamin : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

“McKinley’s Favorite Parrot,” The St Johnsbury Caledonian [St. Johnsbury, VT]. November 5, 1902, p. 7, second column. Accessed online through Chronicling America: St. Johnsbury Caledonian. [volume] (St. Johnsbury, Vt.) 1867-1919, November 05, 1902, Page 7, Image 7 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov).

Maynard, Lucy W. “President Roosevelt’s List of Birds.” Bird-Lore: A Bi-Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Study and Protection of Birds: Official Organ of the Audubon Societies. Vol. XII, no. 2, March-April 1910. As published by Adam Sedgely in BirdNote, April 10, 2014: President Theodore Roosevelt's Bird Checklist for the White House | BirdNote.

Norment, W.M. to Samuel G. Heiskell. February 18, 1921. As published in Heiskell, Andrew Jackson and Early Tennessee History, vol. III (Nashville, TN: Ambrose Printing Company, 1921), pp. 53-54. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: Andrew Jackson and early Tennessee history ... : Heiskell, Samuel Gordon, 1858-1923 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

Rives, Judith Walker [Mrs. William Cabell Rives]. Manuscript autobiography. Library of Congress MSS 37937, William C. Rives papers, Box 130, autobiography page 56.

Roosevelt, Theodore to Joel Chandler Harris. June 9, 1907. As published in Roosevelt, Letters to His Children (ed. Joseph Bucklin Bishop) (New York: Scribner, 1919), pp. 34-35. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: Letters to his children; : Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858-1919 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

The Sky lark: or Gentlemen and ladies' complete songster. Boston: Isaiah Thomas, 1795. Accessed online through the University of Michigan: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=evans;c=evans;idno=N22352.0001.001;node=N22352.0001.001:3;rgn=div1;view=text.

Washington, George to Tobias Lear. March 9, 1787. Accessed online through Founders Online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-01-02-0017.

George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Pocket Book of Cash Expenses, August, 1772 - May, 1773. April 8, 1773. Library of Congress MSS 44693: Reel 116, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw5.116_0993_1064/?sp=59&st=image.

The Diaries of George Washington vol. III, eds. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1976. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/diariesofgeorgew0003wash/page/n7/mode/2up?q=parrot.

SECONDARY

A Way with Words (Martha Barnette and Grant Barrett), “Polly Wanna Cracker?” Waywordradio.org. February 28, 2009. Polly Wanna Cracker? – A Way with Words, a fun radio show and podcast about language (waywordradio.org).

Dessem, Matthew. “All the Presidents’ Pets.” Slate. January 31st, 2021. Presidential pets: The best dogs, cats, possums, racist parrots, and more who ever lived in the White House, and beyond. (slate.com)

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Macaw.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last updated February 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/animal/macaw.

Finan, Pat. “McKinley’s D.C. pets: roosters, parrot.” Tribune Chronicle [Ohio]. February 26, 2018. https://www.tribtoday.com/news/local-news/2018/02/mckinleys-d-c-pets-roosters-parrot/.

Hicks, Hilarie M. “Parroting Historical Research.” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway. August 13, 2018. Parroting Historical Research – Montpelier's Digital Doorway.

“The Great Portrait Rescue: A Historical Whodunit.” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway. August 22, 2019. The Great Portrait Rescue: A Historical Whodunit – Montpelier's Digital Doorway.

Kovalchik, Kara. “Why Do We Call Parrots ‘Polly’?” Mental Floss. March 4, 2014. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/55350/why-do-we-call-parrots-polly.

Schafer, Leanna. “Polly the Parrot.” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway. July 30, 2018. Polly the Parrot – Montpelier's Digital Doorway.

Thompson, Mary V. “Birds.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon: Washington Library Center for Digital History, Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington. Birds · George Washington's Mount Vernon.

Wepman, Dennis. “Hogan, Ernest (1860-12 May 1909).” American National Biography. March 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1803811.

Judith Walker Rives [Mrs. William Cabell Rives], manuscript autobiography, Library of Congress MSS 37937, William C. Rives papers, Box 130, autobiography page 56. And how did “Polly” become the generic name for a pet parrot? mental_floss, sans citation, says that the use of the term can be traced back to English playwright Ben Jonson’s 1605 Volpone (Kara Kovalchik, “Why Do We Call Parrots ‘Polly’?”, Mental Floss, March 4, 2014, Why Do We Call Parrots "Polly"? | Mental Floss). The play, set in Venice, features an English character named Sir Politique Would-Bee (i.e., he would like to be “politic,” or crafty/shrewd) who copies Italian customs in the imperfect and amusing way a parrot copies human speech. Sir Politique is nicknamed “Sir Pol,” he’s parrot-like (I guess you have to read the full play to get it), and so parrots became “Poll Parrot” and also “Polly.” Plausible enough, I suppose? See: Benjamin Jonson, Ben: Jonson his Volpone or the Foxe (London: Thomas Thorppe, 1607), accessed online through the Internet Archive: Ben: Jonson his Volpone or the foxe. 1607 : Jonson, Benjamin : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive/.

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Macaw,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, last updated February 29, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/animal/macaw. I defer to Montpelier’s staff in their identification of Polly as a scarlet macaw. From what I can tell, Dolley’s niece simply described her as a “large Macaw” (Mary Estelle Elizabeth Cutts, Mary Cutts Memoir II, as published in The Queen of America: Mary Cutts’s Life of Dolley Madison [ed. Catherine Allgor] [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012], pp. 133-196, 159, accessed online through the Internet Archive: The queen of America : Mary Cutts's life of Dolley Madison : Cutts, Mary Estelle Elizabeth, 1814-1856 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive); Judith Walker Rives (Polly’s #1 enemy), called her a “great parrot” with “magnificent plumage” (Rives).

Rives.

Not French Stewart, although Hollywood studio execs of the ‘90s missed a huge opportunity for a heartwarming children’s movie about the War of 1812. As quoted in ibid; see also Hilarie M. Hicks, “Parroting Historical Research,” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway, August 13, 2018, https://digitaldoorway.montpelier.org/2018/08/13/parroting-historical-research/.

Ibid. See also: Paul Jennings, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison (Brooklyn: George C. Beadle, 1865), 10, accessed online through the Internet Archive: A colored man's reminiscences of James Madison (archive.org); Montpelier’s superb Hilarie Hicks on “The Great Portrait Rescue: A Historical Whodunit,” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway, August 22, 2019, The Great Portrait Rescue: A Historical Whodunit – Montpelier's Digital Doorway.

Leanna Schafer, “Polly the Parrot,” Montpelier’s Digital Doorway, July 30, 2018, Polly the Parrot – Montpelier's Digital Doorway.

Mary V. Thompson, “Birds,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon: Washington Library Center for Digital History, Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington, Birds · George Washington's Mount Vernon. You can see his handwritten entry for the purchase on the Library of Congress’ website: George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Pocket Book of Cash Expenses, August, 1772 - May, 1773, April 8, 1773, MSS 44693: Reel 116, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw5.116_0993_1064/?sp=59&st=image. It also seems that Washington purchased this bird off a West Indies sea captain, John Cox, who visited Mount Vernon to trade for a few days in 1773. See Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington vol. III (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1976), 171, accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/diariesofgeorgew0003wash/page/n7/mode/2up?q=parrot. Many thanks to Mary Thompson for helping me track this bird down—interested readers should stay tuned for her forthcoming book on animals at Mt. Vernon.

Thompson, “Birds.”

George Washington to Tobias Lear, March 9, 1787, accessed online through Founders Online: From George Washington to Tobias Lear, 9 March 1797 (archives.gov).

Thompson, “Birds”; “Pauvre Madelon,” as published in The Sky lark: or Gentlemen and ladies' complete songster (Boston: Isaiah Thomas, 1795), 38, accessed online through the University of Michigan: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=evans;c=evans;idno=N22352.0001.001;node=N22352.0001.001:3;rgn=div1;view=text.

Washington to Lear, March 9, 1787, note 7.

Hicks, “Parroting.” Cutts, Dolley’s niece, drafted her memoirs of her aunt in the 1850s and describes Polly’s death as recent—see Appendix B.

W.M. Norment to Samuel G. Heiskell, February 18, 1921, as published in Heiskell, Andrew Jackson and Early Tennessee History, vol. III (Nashville, TN: Ambrose Printing Company, 1921), pp. 53-54, 54, accessed online through the Internet Archive: Andrew Jackson and early Tennessee history ... : Heiskell, Samuel Gordon, 1858-1923 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

Pat Finan, “McKinley’s D.C. pets: roosters, parrot,” February 26, 2018, Tribune Chronicle [Ohio], McKinley’s D.C. pets: roosters, parrot | News, Sports, Jobs - Tribune Chronicle (tribtoday.com).

“McKinley’s Favorite Parrot,” The St Johnsbury Caledonian [St. Johnsbury, VT], November 5, 1902, p. 7, second column, accessed online through Chronicling America: St. Johnsbury Caledonian. [volume] (St. Johnsbury, Vt.) 1867-1919, November 05, 1902, Page 7, Image 7 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov). For more about Ernest Hogan, see his American National Biography entry; Dennis Wepman, “Hogan, Ernest (1860-1909”,” March 2010, Hogan, Ernest (1860-1909), minstrel show and vaudeville entertainer and songwriter | American National Biography (anb.org). I refer you also to Hogan’s well-sourced Wikipedia page. By the way, Slate writer Matthew Dessem also discovered the “Washington Post”/”Loretta” discrepancy a few years ago: Dessem, “All the Presidents’ Pets,” Slate, January 31st, 2021, Presidential pets: The best dogs, cats, possums, racist parrots, and more who ever lived in the White House, and beyond. (slate.com).

Lucy W. Maynard, “President Roosevelt’s List of Birds,” in Bird-Lore: A Bi-Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Study and Protection of Birds: Official Organ of the Audubon Societies, vol. XII, no. 2, March-April 1910, as published by Adam Sedgely in BirdNote, April 10, 2014, President Theodore Roosevelt's Bird Checklist for the White House | BirdNote; Theodore Roosevelt to Joel Chandler Harris, June 9, 1907, as published in Letters to his children; : Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858-1919 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive, 34-35, 35.