Dear Reader,

The Roscoe Conkling—Gilded Age Senator from New York, renowned orator, railroad lawyer, erstwhile champion of the political spoils system—had no sons to bear his illustrious name. Despite rumors of prolific adultery, his only known child was a daughter by his long-suffering wife.1 Nevertheless, a host of nineteenth-century American parents honored the statesman’s virtues by bestowing “Roscoe Conkling” on their infant sons. America’s next century can be traced through the vibrant lives of these Roscoe Conklings—the fight of black Americans for civil rights, the growing role of Hollywood in national culture, and the country’s participation in two world wars.

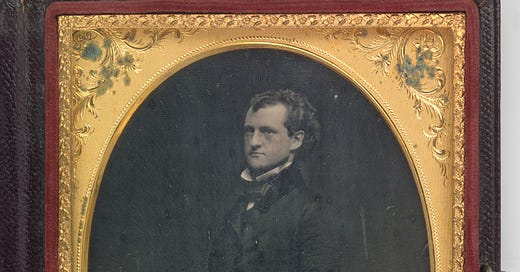

The first Roscoe Conkling was in fact not quite the first Roscoe Conkling. Our subject was named for an older brother who died in infancy a little more than a year before the future Senator arrived on the scene in Albany, New York in 1829. The first boy came by his name courtesy of William Roscoe, a British writer, abolitionist, and Renaissance historian read by mother Eliza when she was pregnant.2 The family patriarch was a prominent New York judge, and our young Roscoe became District Attorney of Oneida County at the tender age of twenty before going into private practice.3

Figure I: Daguerreotype of Roscoe Conkling, ca. 1855

Roscoe Conkling, ca. 1855, quarter-plate daguerreotype, unknown artist, collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed online through the National Portrait Gallery: https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.95.101?destination=node/63231%3Fedan_q%3Droscoe%2520conkling.

He strode into a troubled antebellum Congress in 1859 under the banner of the new anti-slavery Republican party. Briefly unseated during the Civil War by a so-called “Peace Democrat” seeking a negotiated end to the conflict, Conkling avoided military service but secretly engaged in a lucrative sideline in cotton speculation.4 The proud and fastidious Conkling wouldn’t “put a bank-bill into his wallet until it was folded” to his precise specifications. As a senator, he enjoyed lordly control over federal job appointments in New York State.5

Conkling earned a reputation for supporting civil rights for the South’s newly emancipated black population. Indeed, one of the earliest baby Roscoe Conklings was the son of his Senate colleague Blanche Bruce of Mississippi, the first black senator to serve a full term in Congress.6 When the other (white) senator from Mississippi refused to introduce Bruce to the president of the Senate, as dictated by tradition, Conkling stepped in to perform the duty.7 Roscoe Conkling Bruce was born in 1879 at the vanguard of a generation of black Roscoe Conklings.

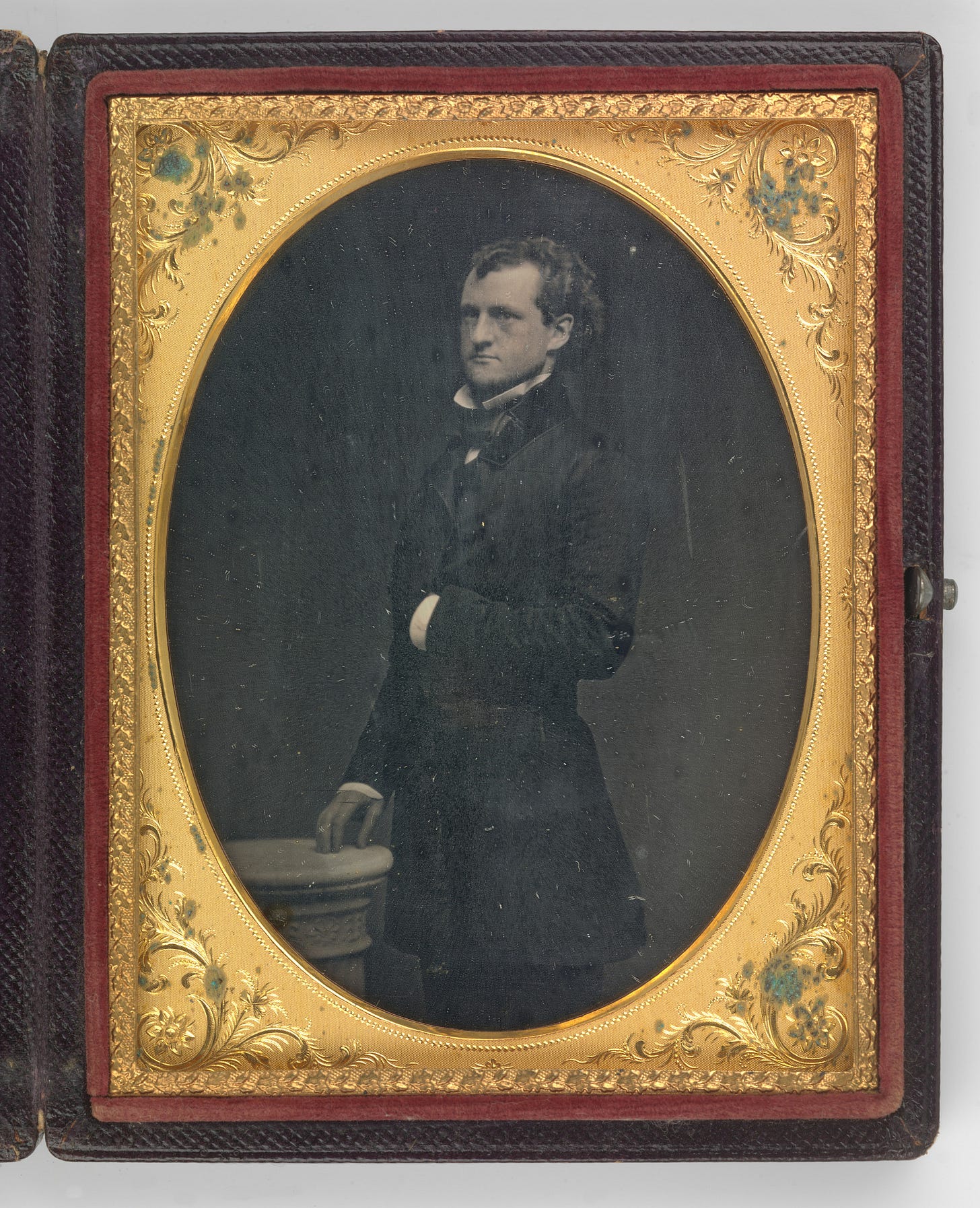

Senator Conkling resigned his seat in May 1881 as a protest in the intra-party battle between Republican “Stalwarts,” who advocated the time-honored system that allowed political appointees to bestow favors on supporters, and reform-minded “Half-Breeds” who wanted to regularize civil service employment. In July of that year, President Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau, a mentally ill “Stalwart” who had repeatedly demanded a foreign appointment in Paris or Vienna. Killing Garfield, Guiteau reasoned, would empower Garfield’s vice president (and former Conkling protégé) Chester A. Arthur to finally grant him the position. Things didn’t work out exactly as either Conkling or Guiteau expected: the New York state legislature failed to return Conkling to the Senate, and Guiteau was executed.8

Figure II. “A Harmless Explosion”: Roscoe Conkling Resigns from the Senate, May 1881

Joseph Keppler, “A Harmless Explosion” [cartoon], Puck, May 25th, 1881. As published in Keppler, Cartoons from Puck (New York: Keppler and Schwarzmann, 1893). Accessed online through Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59604/59604-h/59604-h.htm. Full color view (pages 204-205) and commentary (page 198) as published in Puck available through Google Books here.

Don’t weep too much for either of them. Guiteau famously recited a poem on the gallows declaring “I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad” and Conkling went back to a successful career as a lawyer with considerable political influence.9 Perhaps his most lasting contribution to American jurisprudence was an 1882 Supreme Court case in which he represented the Southern Pacific Railway and advanced the argument that the Fourteenth Amendment protected corporations—essentially, that corporations are people.10

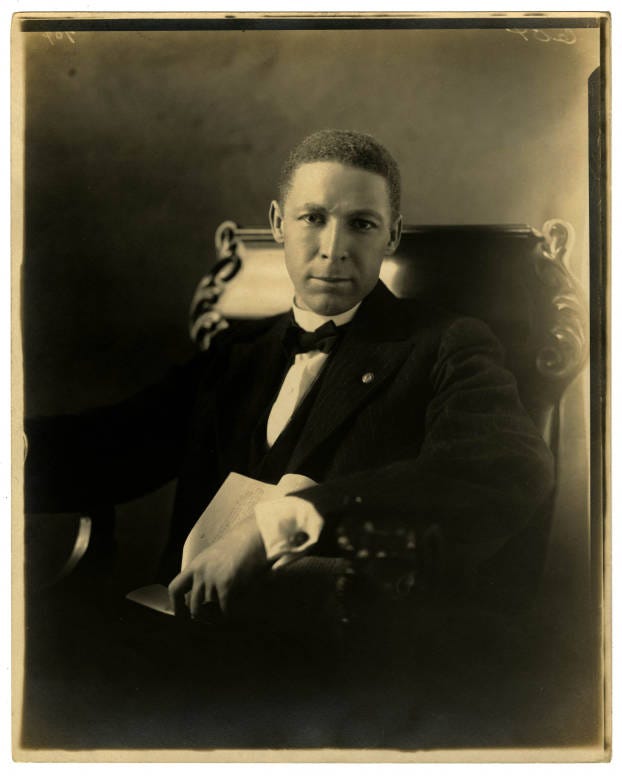

Conkling’s rhetorical abilities lived on through many of his namesakes, perhaps none more notable than Roscoe Conkling Simmons. Born to a pair of successful black educators in Mississippi just weeks after his namesake’s Senate resignation, Roscoe Simmons became a nephew-by-marriage of Booker T. Washington in 1893.11 Simmons would later claim that his uncle rehearsed his famous 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech before him, in which Washington tacitly accepted segregation as prerequisite for economic opportunity: “in all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”12 Whether or not Washington jumpstarted his interest in public speaking, Simmons grew up to be a spellbinding orator whose speeches drew black and white audiences by the thousands.13

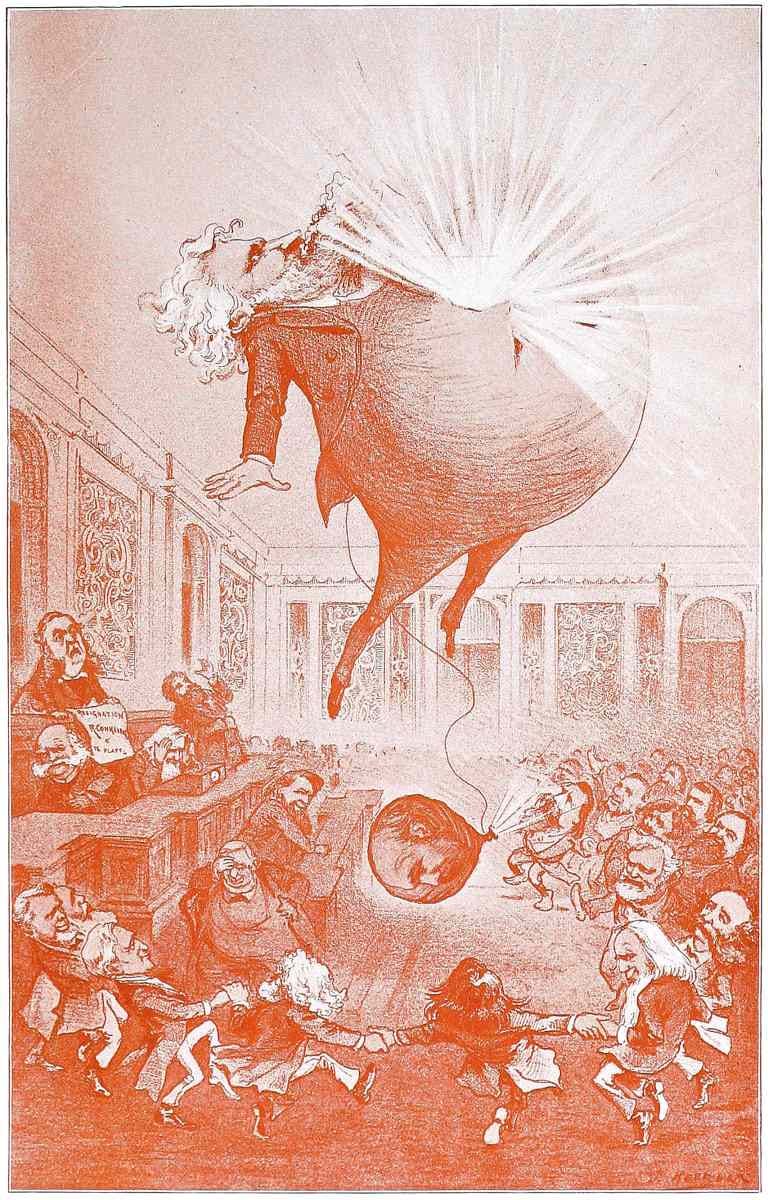

Roscoe Conkling Bruce, an academic standout and Harvard grad, also entered Washington’s powerful orbit. While still an undergraduate, Bruce joined functionaries like Simmons in quietly keeping tabs on Washington’s political enemies.14 Bruce served as academic director at Washington’s Tuskegee Institute for four years before returning to his hometown of Washington, D.C. to work in the city’s segregated public schools.15 “The closing of [white] accommodations is really the opening for black business men of the doors of opportunity,” he told D.C. high school graduates in 1903—including an aspiring dentist named Roscoe Conkling Brown.16

Figure III: Roscoe Conkling Bruce Speaks at Roscoe Conkling Brown, Sr.’s High School Graduation, 1903

Excerpt from “Our Colored Schools,” The Colored American [Washington, D.C.], June 20, 1903, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83027091/1903-06-20/ed-1/seq-4/. Page 1 of the article is here: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83027091/1903-06-20/ed-1/seq-1/.

“You are pledged not to pick your way daintily in the soft places of the earth,” Bruce warned his young audience at the dawn of the twentieth century.17 And indeed, the coming decades would not prove particularly dainty. Europe plunged the world into war in 1914; Roscoe Conkling’s own grandson (not a Roscoe but a Walter George after his father) leapt into the conflict ahead of his country, serving in the British Army with distinction in 1916.18

The United States entered the war in April 1917. Congress quickly passed the Selective Service Act, instituting a nationwide draft for the first time. The head of New York City’s draft board was none other than Roscoe Seely Conkling, born to the surname in 1884 (his father was reportedly a cousin of the senator).19 Conkling followed in his famous namesake’s footsteps and became a lawyer—but deviated slightly from the earlier Conkling’s example by gaining a reputation for tireless work uncovering fraud and corruption.20 Roscoe Conkling Simmons embarked on a patriotic speaking tour and even traveled to France to report on black soldiers serving in Europe. Openings in defense industry jobs gave new impetus to his speeches and column in the Chicago Defender urging black Southerners to move north to escape Jim Crow.21

Figures IV and V. Roscoe Seely Conkling, ca. 1915-1920 (left) and Roscoe Conkling Simmons, 1920 (right)

Left: Bain News Service, “Roscoe Conkling,” ca. 1915-1920, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014705059/.

Right: Arthur P. Bedou, Portrait of Roscoe Conkling Simmons, photograph, 1920, Arthur P. Bedou Photographs Collection, Xavier University of Louisiana Archives, https://cdm16948.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16948coll8/id/144/rec/2.

Roscoe Conkling Bruce did not emerge from the war covered in glory. By the late nineteen-teens, he was instead embroiled in scandal. A growing number of D.C. parents disagreed with Bruce’s “Bookerite” approach focusing on technical education rather than liberal arts, and they certainly disagreed with his decision to allow a shady German anthropologist to take nude photos of students.22

Bruce’s scandals were local, but those of Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle, born 1887, were decidedly not.23 In 1921, “Fatty” Arbuckle was one of the world’s first movie stars, beloved for his antics in silent comedies. Then a young actress died after one of his parties in 1921 and all hell broke loose—Arbuckle was charged with murder, then manslaughter, and finally exonerated with an apology from the jury.24 The public outcry about the Arbuckle affair and other contemporary celebrity scandals was great enough that in 1922 President Warren G. Harding placed postmaster Will Hays in charge of an effort to clean up Hollywood’s morals.25 The movie industry was permanently changed by Hays’ rules for what could be shown on film, but Arbuckle’s reputation never recovered and he died in 1933.26

Figure VI. Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle, ca. 1920-1925

Bain News Service, “R. Arbuckle,” ca. 1920-1925, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014713223/.

The end of Roscoe Arbuckle did not herald the end of his brethren’s role in American history. When the U.S. was attacked by the Empire of Japan in December 1941, Roscoe Conklings sprang into action.27 Roscoe Seely Conkling again assumed an important role in administering the draft.28 Volunteering for service in the Army Medical Corps was surgeon Roscoe Conkling Giles, the first black graduate of Cornell’s medical school.29 Roscoe Conkling Brown, Jr. (son of the accomplished dentist and public health professional who had graduated high school in 1903) joined the legendary Tuskegee Airmen and flew more than 68 combat missions in the Mediterranean. Brown, Jr. would go on to become a professor, talk show host, and civic leader, serving as an advisor to David Dinkins, the first black mayor of New York City.30

Figure VII. Roscoe Conkling Brown, Jr. (far left) as Tuskegee Airman, 1945

Toni Frissell, [Tuskegee airmen Roscoe C. Brown, Marcellus G. Smith, and Benjamin O. Davis, Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945], Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2007675072/.

Roscoe Conklings have exerted a powerful influence over the public life of our nation. In the immortal words of Frederick Douglass: “Well, why are we here? What was Roscoe Conkling to us or we to Roscoe Conkling?”31 Indeed, we have barely begun to scratch the surface.

Sincerely,

Miss Remember

SOURCES

Roscoe Conkling (1829-1888)

Primary

Conkling, Alfred Ronald. The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling, Orator, Statesman, Advocate. New York: Charles L. Webster and Company, 1889. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifelettersofros00inconk/page/6/mode/2up.

Decatur Weekly Republican [Decatur, IL]. September 21, 1882. Page 3, far left column, second item. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/decatur-weekly-republican-1882-09-21/page/I/mode/2up?q=wilde.

Douglass, Frederick. Eulogy for Roscoe Conkling, April 25th, 1888 [manuscript and typescript]. Frederick Douglass Papers, Library of Congress, mss11879, box 25, reel 16. Accessed online through the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1187900459/.

Godding, W.W. The Last Chapter in the Life of Guiteau. Washington, D.C.: reprint from the Alienist and Neurologist, St. Louis, October, 1882. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/101648406.nlm.nih.gov/mode/2up.

“More Light! Sprague-Conkling Scandal.” Narragansett Herald [Narragansett, RI]. August 23, 1879. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063989/1879-08-23/ed-1/seq-2/.

“Roscoe Conkling Dead.” Waterbury Evening Democrat [Waterbury, CT]. April 18, 1888. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94053256/1888-04-18/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Sprague-Conkling.” Narragansett Herald [Narragansett, RI]. August 16, 1879. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063989/1879-08-16/ed-1/seq-2/.

“Walter G. Oakman, Jr., Wins D.S.O. at Cambrai.” The New-York Tribune [New York City, NY]. December 19, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-12-19/ed-1/seq-4/.

Secondary

Arrington, Todd. “Stalwarts, Half Breeds, and Political Assassination.” The Garfield Observer [newsletter of the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, Mentor, OH], November 2012. Republished by the National Park Service online at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/stalwarts-half-breeds-and-political-assassination.htm.

Broxmeyer, Jeffrey D. “Roscoe Conkling’s Wartime Cotton Speculation.” New York History, Vol. 96, No. 2 (Spring 2015), pp. 167-181. Accessed online through JStor: https://www.jstor.org/stable/newyorkhist.96.2.167/.

Bullard, Melissa Meriam. “Roscoe’s Renaissance in America.” In Roscoe and Italy: The Reception of Italian Renaissance History and Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, ed. Stella Fischer. London: Routledge, 2012, pages 217-240.

Graham, Howard Jay. “The ‘Conspiracy Theory’ of the Fourteenth Amendment.” The Yale Law Journal, Jan., 1938, Vol. 47, No. 3 (Jan. 1938), pp. 371-403. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/791947.pdf.

Jordan, David M. Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice in the Senate. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/roscoeconklingof00jord/page/n5/mode/2up.

Russell, Charles Edward. Blaine of Maine: His Life and Times. New York: Cosmopolitan Book Club, 1931. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/blaineofmainehis0000char/.

Roscoe Conkling Bruce (1879-1950)

Primary

Bruce, Roscoe C. “Service of the Educated Negro.” Commencement speech for the M Street School at Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, Washington, D.C., June 16, 1903. Printed by the Tuskegee Institute. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/serviceofeducate00bruc/page/n1/mode/2up.

“Conkling’s Namesake,” The Loup City Northwestern [Loup City, Nebraska]. January 12, 1900. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2018270203/1900-01-12/ed-1/seq-4.

Secondary

Foner, Eric. “Rise and Fall of the House of Bruce (review).” The Washington Post. July 2, 2006. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/29/AR2006062901352.html.

Gates, Henry Louis and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, eds. “Roscoe Conkling Bruce, Sr.” In Harlem Renaissance Lives from the African American National Biography, pages 84-85. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009. Accessed online through Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=E_vRLcgEdGoC&pg=PA84#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Miller, Ben. “Blanche Bruce’s Washington.” Boundary Stones: WETA’s Local History Website. July 21, 2021. https://boundarystones.weta.org/2021/07/21/blanche-bruces-washington.

Graham, Lawrence Otis. The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America’s First Black Dynasty. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

Roscoe Conkling Simmons (1881-1951)

Primary

“Col. Simmons is Back Home Again: “Roscoe” Welcomed Home by Chicagoans.” The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition). April 12, 1919. Accessed online through ProQuest Historical Newspapers: https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/col-simmons-is-back-home-again/docview/493381415/se-2/.

“Simmons Thrills Vast Audience.” The Colorado Statesman [Denver, CO]. July 14, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025514/1917-07-14/ed-1/seq-1/.

Washington, Booker T. Address at Cotton States and International Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia, September 18, 1895. Accessed online through George Mason University’s History Matters: https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/.

Secondary

Kaye, Andrew M. “Colonel Roscoe Conkling Simmons and the Mechanics of Black Leadership.” Journal of American Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Apr., 2003), pp. 79-98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27557255.

“Roscoe Conkling Simmons and the Significance of African American Oratory.” The Historical Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Mar., 2002), pp. 79-102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3133631.

Boulware, Marcus H. “Roscoe Conkling Simmons: The Golden Voiced Politico.” Negro History Bulletin, Vol. 29, No. 6 (March, 1966), pp. 131-132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24766396.

Roscoe Seely Conkling (1884-1956)

Primary

“Bribery Charge Causes Ousting of Draft Board.” New-York Tribune [New York, NY]. August 11, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-08-11/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Conkling-Woodbury.” The Oxford Democrat [Paris, ME]. October 31, 1911. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83009653/1911-10-31/ed-1/seq-2/.

“The Jewish Conscripts,” The Jewish Daily News [Yiddish; New York, NY]. September 12, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063496/1917-09-13/ed-1/seq-1/).

“Mrs. Conkling Dies in New Rochelle.” Poughkeepsie New Yorker [Poughkeepsie, NY]. September 13, 1945. Accessed online through FindAGrave.com, uploaded by Patrick Arthur Teater, Sr.: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/219052134/priscilla-conkling#view-photo=217826288.

“One in Five Will Fight, Draft Tables Now Show.” New-York Tribune [New York, NY]. August 6, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-08-06/ed-1/seq-1/.

Owen, Russell Dyer. “Conscripts Silent and Earnest as They Face Test,” The Sun [New York, NY]. August 12, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030431/1917-08-12/ed-1/seq-48/.

“Roscoe Conkling, Lawyer, Is Dead,” New York Times, September 16, 1956.

Roscoe Conkling Brown Sr. (1884-1962) and Jr. (1922-2016)

Primary

“Health Week Committee Begins Work.” The Washington Tribune [Washington, D.C.] November 26, 1926. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062236/1926-11-26/ed-1/seq-7/.

“M Street School Holds Commencement.” The Washington Times [Washington, D.C.]. June 17, 1903. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1903-06-17/ed-1/seq-3/.

“Meets at Dunbar School.” The Evening Star [Washington, D.C.]. May 11th, 1921. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1921-05-11/ed-1/seq-14/.

“Negro Health Rally To Hear Dr. Brown.” The Evening Star [Washington, D.C.]. March 30, 1939. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1939-03-30/ed-1/seq-22/

“Officers of the Battalion of Cadets M Street High School,” The Colored American [Washington, D.C.], June 13, 1903. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83027091/1903-06-13/ed-1/seq-4/.

“Our Colored Schools.” The Colored American [Washington, D.C.], June 20, 1903. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83027091/1903-06-20/ed-1/seq-4/.

Roberts, Sam. “Roscoe C. Brown Jr., Tuskegee Airman and Confidant to New York Politicians, Dies at 94.” New York Times. July 5, 2016. Accessed online through Archive.org: https://web.archive.org/web/20160706033645/http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/06/nyregion/roscoe-c-brown-jr-tuskegee-airman-and-confidant-to-new-york-politicians-dies-at-94.html/.

Roscoe Conkling Brown, Sr. World War II Draft Registration Card. Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II (Fourth Registration) for the District of Columbia, records of the Selective Service System, Record Group Number 147, Box or Roll Number 009. National Archives and Records Administration, St. Louis, Missouri. Accessed online through Ancestry.com: https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/17611985:1002.

Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle (1887-1933)

Primary

Beal, John R. “Arbuckle is Found Dead in Bed by Wife.” The Waterbury Democrat [Waterbury, CT]. June 29, 1933. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014085/1933-06-29/ed-1/seq-1/.

“In the Editor’s Letter-Box: More About ‘Fatty.” Washington Herald [Washington, D.C.]. April 30, 1922. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1922-04-30/ed-1/seq-17/.

“Today” [page 2]. Washington Herald [Washington, D.C.]. December 26, 1922. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1922-12-26/ed-1/seq-2/#).

“Will H. Hays Signs to Direct Movies.” New York Times. January 19, 1922.

Secondary

Merritt, Greg. Room 1219: The Life of Fatty Arbuckle, the Mysterious Death of Virginia Rappe, and the Scandal that Changed Hollywood. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/room1219lifeoffa0000merr/page/n3/mode/2up.

Oderman, Stuart. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle: A Biography of the Silent Film Comedian, 1887-1933. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., 1994. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/roscoefattyarbuc0000oder/.

Other Roscoe Conklings Mentioned

“Roscoe Conkling Giles, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.I.C.S., 1890-1970.” Journal of the National Medical Association (May 1970), pages 254-256. Accessed online through the National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2611824/pdf/jnma00511-0118.pdf.

The daughter was art collector Eliza “Bessie” Conkling Oakman (1856-1931); the long-suffering wife was Julia Seymour (1827-1893), sister of two-time New York governor and failed Democratic presidential candidate Horatio Seymour (1810-1886). In his 1931 biography of James G. Blaine, Charles Edward Russell records a rumor that Conkling threatened to kill a newspaper editor who was going to publish a list of his romantic dalliances. Freedom of the press be damned: “There was in Mr. Conkling’s voice something so unspeakably fierce and cruel and in his savage gaze something so appalling that few men…could have withstood him,” recalled the editor’s assistant (Charles Edward Russell, Blaine of Maine: His Life and Times [Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971], 116).

Alfred Ronald Conkling, The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling, Orator, Statesman, Advocate (New York: Charles L. Webster and Company, 1889), 7, accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifelettersofros00inconk/page/6/mode/2up.

Eliza Conkling was far from alone in admiring William Roscoe, who would die in 1830 just a year after her second Roscoe Conkling’s birth. The Liverpool native was a household name in the United States for his American-style rise from humble beginnings to business success, scholarship, and civic virtue. See Melissa Meriam Bullard, “Roscoe’s Renaissance in America” in Roscoe and Italy: The Reception of Italian Renaissance History and Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, ed. Stella Fischer (London: Routledge, 2012), pages 217-240.

Life and Letters, 19.

Historian Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer snooped through Conkling and his business partners’ federal tax returns, finding evidence to suggest Conkling made the equivalent of almost $400,000 in today’s money off of cotton acquired in Memphis during the war. See Broxmeyer, “Roscoe Conkling’s Wartime Cotton Speculation.” New York History, Vol. 96, No. 2 (Spring 2015), pp. 167-181, 177, accessed online through JStor: https://www.jstor.org/stable/newyorkhist.96.2.167/.

Daniel Batchelor, quoted in Life and Letters, 20.

Scholar Lawrence Otis Graham traces the fascinating history of the Bruce family in The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America’s First Black Dynasty (New York: HarperCollins, 2006).

“Conkling’s Namesake,” The Loup City Northwestern [Loup City, Nebraska]. January 12, 1900. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2018270203/1900-01-12/ed-1/seq-4. Graham’s contemporary source for this incident is the March 6th, 1875 edition of the National Republican [Washington, D.C].

Todd Arrington, “Stalwarts, Half Breeds, and Political Assassination,” The Garfield Observer [newsletter of the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, Mentor, OH], November 2012, republished by the National Park Service online at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/stalwarts-half-breeds-and-political-assassination.htm.

Guiteau as quoted in W.W. Godding, The Last Chapter in the Life of Guiteau (Washington, D.C.: reprint from the Alienist and Neurologist, St. Louis, October, 1882), 6-7. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/101648406.nlm.nih.gov/mode/2up.

Political scientist Howard Jay Graham documented the history of Conkling’s “conspiracy theory” of the Fourteenth Amendment (that its framers—including Conkling—wrote it to protect corporations) in a 1938 article in the Yale Law Journal. See Graham, “The ‘Conspiracy Theory’ of the Fourteenth Amendment,” The Yale Law Journal, Jan., 1938, Vol. 47, No. 3 (Jan. 1938), pp. 371-403, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/791947.pdf.

Conkling’s argument was accepted by the Supreme Court in the 1886 case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad. Before argument, Chief Justice Morrison Waite announced “The Court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment….which forbids a state to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws applies to these corporations. We are all of opinion that it does.” See “Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co., 118 U.S. 394 (1886),” Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/118/394/#396.

Historian Andrew Kaye also notes that Simmons was flexible with his birthdate and birthplace in order to appeal to different audiences at different times. See Kaye, “Colonel Roscoe Conkling Simmons and the Mechanics of Black Leadership,” Journal of American Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Apr 2003), pp. 79-98, 83-84. Access online through JStor: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27557255.

Simmons’ maternal aunt and Washington’s third wife, Margaret Murray, was an accomplished educator and activist who helped build the success of Washington’s Tuskegee Institute: see her Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame entry for a more complete bibliography.

Washington, Address at Cotton States and International Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia, September 18, 1895, accessed online through George Mason University’s History Matters: https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/. You can listen to a 1908 recording of Washington repeating part of this speech through the Library of Congress’ website: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/multimedia/booker-t-washington.html.

Despite his achievements, Washington came under heavy criticism in his day and ours for his “accomodationist” approach towards white racism. That legacy is perhaps most strikingly captured by artist Martin Puryear’s 1996 sculpture A Ladder for Booker T. Washington (or perhaps I just think that because an old poster of it hung outside my history classroom in high school).

See especially Kaye, “Roscoe Conkling Simmons and the Significance of African American Oratory,” The Historical Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Mar 2002), pp. 79-102, 88-91, for an overview of Simmons’ popularity. Access online through JStor: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3133631.

Graham, The Senator and the Socialite, 159. For Simmons’ role in the “Tuskegee Machine,” see Kaye, “Simmons and the Mechanics of Black Leadership,” 85-86.

Gates, Henry Louis and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, eds., “Roscoe Conkling Bruce, Sr,” in Harlem Renaissance Lives from the African American National Biography, pages 84-85 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009), 84, accessed online through Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=E_vRLcgEdGoC&pg=PA84#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Roscoe C. “Service of the Educated Negro,” commencement speech for the M Street School at Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, Washington, D.C., June 16, 1903, printed by the Tuskegee Institute, 15. Accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/serviceofeducate00bruc/page/n1/mode/2up.

In Brown Junior’s obituary, Times reporter Sam Roberts claimed that Brown Senior changed his name in order to honor the legacy of the New York senator. From what I can tell, Brown Senior was a Roscoe Conkling dating back to at least his high school days in D.C.: “Officers of the Battalion of Cadets M Street High School,” The Colored American [Washington, D.C.], June 13, 1903. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83027091/1903-06-13/ed-1/seq-4/.

Bruce, “Service,” 17.

“Walter G. Oakman, Jr., Wins D.S.O. at Cambrai.” The New-York Tribune [New York City, NY]. December 19, 1917. Accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-12-19/ed-1/seq-4/.

Conkling characterized as Roscoe 1.0’s nephew: “Conkling-Woodbury,” The Oxford Democrat [Paris, ME], October 31, 1911, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83009653/1911-10-31/ed-1/seq-2/.

Conkling’s father characterized as Roscoe 1.0’s cousin: “Roscoe Conkling, Lawyer, Is Dead,” New York Times, September 16, 1956. I dipped my toe into the documented Conkling gene pool trying to sort this one out but quickly gave up.

Russell Dyer Owen of the New York Sun wrote in August 1917: “Mr. Conkling, when not at his office working day and night, has been dashing about the city in an automobile, speeding up lagging [examination] boards, straightening out snarls in the method of procedure and generally inspiring board members to greater efforts” (Owen, “Conscripts Silent and Earnest as They Face Test,” The Sun [New York, NY], August 12, 1917, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030431/1917-08-12/ed-1/seq-48/.)

A sampling of Conkling’s WWI career: chasing down missing documents from a recruitment center (“One in Five Will Fight, Draft Tables Now Show,” New-York Tribune [New York, NY]. August 6, 1917, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-08-06/ed-1/seq-1/), chasing down crooked draft exemptors by night (“Bribery Charge Causes Ousting of Draft Board,” New-York Tribune [New York, NY], August 11, 1917, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1917-08-11/ed-1/seq-1/), arguing for Jewish recruits’ furloughs for the Jewish High Holidays (“The Jewish Conscripts,” The Jewish Daily News [Yiddish; New York, NY], September 12, 1917, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063496/1917-09-13/ed-1/seq-1/).

Kaye, “Simmons and the Significance of African-American Oratory,” 87. For a glowing writeup of Simmons’ wartime oratory, see “Simmons Thrills Vast Audience,” The Colorado Statesman [Denver, CO], July 14, 1917, ccessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025514/1917-07-14/ed-1/seq-1/. On Simmons’ return from Europe, see “Col. Simmons is Back Home Again: “Roscoe” Welcomed Home by Chicagoans.” The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition), April 12, 1919, ccessed online through ProQuest Historical Newspapers: https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/col-simmons-is-back-home-again/docview/493381415/se-2/.

A quick search of Chronicling America during the war years will turn up plenty more praise and criticism of Simmons.

Graham, Chapter 18. You can also trace the scandal through the digitized archives of the Washington Bee, whose editor vehemently disliked Bruce: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025890/.

Deposed and humiliated, Bruce took a job in West Virginia and ultimately relocated his family to New York.

Wikipedia cites The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder for the claim that Arbuckle’s father named his baby Roscoe Conkling because the politician was a known adulterer and Arbuckle suspected that his wife had been unfaithful. To be completely honest with you, Reader, I thought I had found this (equally uncited) claim in the book but didn’t write down the page number. Now I can’t find it again. We are all bereft.

What I can tell you is that in the early 1880s Conkling was a respondent in the high-profile divorce case of Kate Chase Sprague (daughter of Supreme Court justice Salmon P. Chase) and her husband William Sprague. The Narragansett Herald reported that Mr. Sprague chased Conkling off the premises of the Spragues’ Rhode Island beach house with a gun. For the origins of the whole sordid affair, see: “Sprague-Conkling,” Narragansett Herald [Narragansett, RI], August 16, 1879, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063989/1879-08-16/ed-1/seq-2/; “More Light! Sprague-Conkling Scandal,” Narragansett Herald [Narragansett, RI], August 23, 1879, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063989/1879-08-23/ed-1/seq-2/.

Conkling’s big scandal coincided with the first U.S tour of young Irish poet Oscar Wilde, who told a newspaper that he wanted to meet the disgraced politician because they were both getting bad press. See Decatur Weekly Republican [Decatur, IL], September 21, 1882, page 3, far left column, second item, accessed online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/decatur-weekly-republican-1882-09-21/page/I/mode/2up?q=wilde.

The most recent work on the case that I’ve read is Greg Merritt’s 2013 Room 1219: The Life of Fatty Arbuckle, the Mysterious Death of Virginia Rappe, and the Scandal that Changed Hollywood (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013), accessible online through the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/room1219lifeoffa0000merr/page/n3/mode/2up. Merritt offers his theory about what happened between Arbuckle and the actress Virginia Rappe on pages 356-358.

You can read parts one and two of the court transcripts from Arbuckle’s initial indictment on the Internet Archive. A few more interesting reads from contemporary newspapers: an “anti-reformer” writes into the Washington Herald to protest Hays’ attempt to ban Arbuckle films (“More About ‘Fatty,’” In the Editor’s Letter-Box, Washington Herald [Washington, D.C.], April 30, 1922, accessible through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1922-04-30/ed-1/seq-17/); later that year the Herald covers Arbuckle’s acquittal and Hays’ reinstatement of his movies (“Today” [page 2], Washington Herald [Washington, D.C.], December 26, 1922, accessible online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1922-12-26/ed-1/seq-2/#).

“Will H. Hays Signs to Direct Movies,” New York Times, January 19, 1922. Australia’s Flinders University is home to the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) digital archives and has a good overview of the changes of Hays’ era: https://library.flinders.edu.au/mppda.

John R. Beal, “Arbuckle is Found Dead in Bed by Wife,” The Waterbury Democrat [Waterbury, CT], June 29, 1933, accessed online through Chronicling America: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014085/1933-06-29/ed-1/seq-1/.

Unlike Roscoe Conkling himself, who sat out the Civil War despite the heroic service of his brother Frederick in the Union Army and the existence of an infantry regiment unit called “Conkling’s Rifles” in honor of Roscoe (see Broxmeyer, 169-70).

Conkling “was a member of the Presidential Appeals Board of the Selective Service System” during WWII. See “Roscoe Conkling, Lawyer, Is Dead,” New York Times, September 16, 1956.

An Albany native like his namesake. See “Roscoe Conkling Giles, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.I.C.S., 1890-1970,” Journal of the National Medical Association (May 1970), 254-256, accessed online through the National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2611824/pdf/jnma00511-0118.pdf.

Sam Roberts, “Roscoe C. Brown Jr., Tuskegee Airman and Confidant to New York Politicians, Dies at 94,” New York Times, July 5, 2016, accessed online through Archive.org: https://web.archive.org/web/20160706033645/http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/06/nyregion/roscoe-c-brown-jr-tuskegee-airman-and-confidant-to-new-york-politicians-dies-at-94.html/.

Douglass uncharacteristically wrote Roscoe Conkling’s eulogy like a high schooler trying to hit a word count: he spends two pages listing recently deceased and soon-to-die public figures before praising Conkling for being physically “symmetrical” and “an American citizen.” See Douglass, eulogy for Roscoe Conkling [manuscript and typeset], April 25, 1888, Frederick Douglass papers, Library of Congress. Page 4 of typeset speech: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss11879.25004/?sp=11&st=image.